Uncovering JAPA

Covenants, Codes, Restrictions, and Your Own Backyard

As residents of single-family neighborhoods can attest, yards can be a contentious space. Residential yards influence neighborhood aesthetics and recreation while also serving important ecological functions like regulating hydrology.

However, residents whose yards do not conform risk interrupting the "aesthetic harmony" of their neighborhood and can face social or even legal consequences.

Aesthetic and ecological priorities are often at odds with issues like water usage, forcing residents to weigh neighborhood expectations against environmental factors. And they must weigh the influence of several actors and institutions on their decisions, from neighbors to local municipal planners.

In "How Do Homeowners Associations Regulate Residential Landscapes?" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 86, No. 1), authors V. Kelly Turner and Matthew Stiller explore one such institution that rarely receives academic attention concerning yard ecology: the homeowners association (HOA).

HOAs: Aesthetics Over Environment Rules

HOAs are neighborhood-level institutions that purport to represent a residential community's broader interests by requiring homeowners to comply with legally enforceable covenants, codes, and restrictions (CCRs) that provide minimal architectural and landscaping standards designed to protect neighborhood home values from the decisions of anyone homeowner.

The authors note that HOAs currently govern 60 percent of all new single-family housing starts.

The authors reviewed a sample of CCR documents within Maricopa County, Arizona, which contains most of the area around Phoenix. They observed that the number of new HOAs, the length of CCRs, and the number of clauses regulating yards have increased over time, but that the proportion of CCRs explicitly containing landscaping clauses is relatively low.

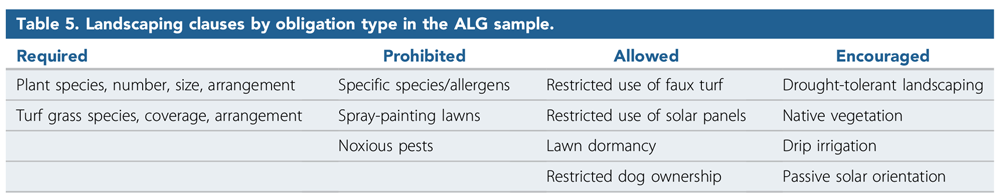

Of those that did contain these clauses, Turner and Stiller examine their nuances using an Institutional Grammar approach that examines the extent to which CCR language "generate[s] regularities in patterns of behavior" — that is, whether it is prohibited or merely discouraged. (See the table below).

With this nuance, they find that HOAs tend to forcefully regulate aesthetics while less forcefully encouraging water saving, suggesting that the association's main goals are rarely environmental.

Table 5: Landscaping clauses by obligation type in the ALG sample.

One of the authors' most significant findings is that many CCRs reference external architecture and landscape guidelines (ALGs) rather than expanding on these guidelines within the documents, even though many ALGs are not publicly recorded with the CCR.

This means "there is no public record of a major source of land use regulations for a majority and growing share of single-family residential land."

HOA Contracts Shape Home Landscapes

While the severity of this situation varies depending on the restrictiveness of the CCR and the likeliness of a HOA to enforce it, the framework itself is concerning given the often reactionary nature of single-family residential neighborhood politics.

As the authors point out, planners need to consider how CCRs function not only as private contracts but also essentially as land use laws governing aesthetics and ecology at the scale of the residential neighborhood — which is not an insignificant form of governance.

Particularly as planners seek to encourage environmentally sustainable homeowner practices, they will need to understand how these practices may conflict with or can be supported by existing CCRs.

Top image: Getty Image photo.