Uncovering JAPA

LGBTQ Communities and Historic Preservation

Literature on the development of LGBTQ communities in urban areas has long linked these communities (and particularly gay men) with the practices of historic preservation.

In their article “Uncovering the Relationship Between Historic Districts and Same-Sex Households” in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 86, No. 4), authors Kelly L. Kinahan and Matthew H. Ruther set out to test common qualitative observations with quantitative methods.

As the story often goes, as LGBTQ communities have become more visible in many American cities since the 1960s, gay men have often chosen to live in affordable neighborhoods with architecturally significant housing stocks, which they preserve in an effort to maintain their historical merit and (advertently or not) raise local home values.

While this has led to upward mobility for many same-sex households as their home values rose, others have critiqued this preservation for coming at the expense of local low-income communities who can’t afford rising rents and housing prices and are thus pushed out.

Gay Gentrification Displaces Low-income Residents

This critique also takes on a racial dimension in that the most visible gay men moving in are often white, while those pushed out of the neighborhood are disproportionately communities of color.

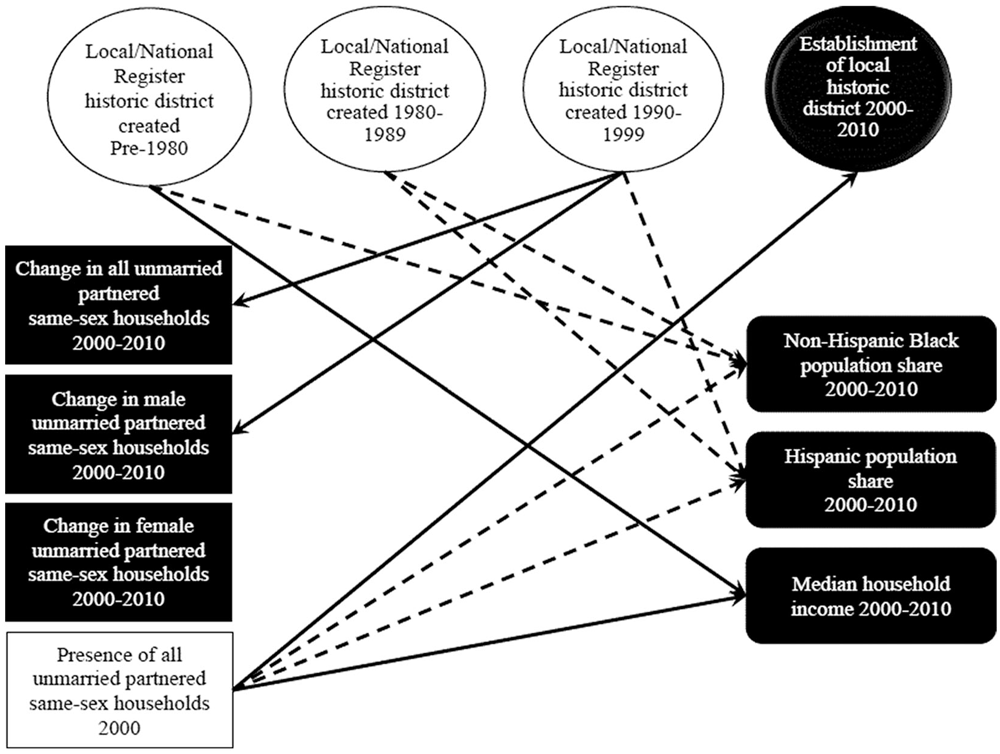

The authors reach three conclusions from their analysis of census data on unmarried partnered same-sex households (UPSSHs), percentage of Black and Hispanic households, and median household income from 2000 and 2010 as well as several decades of data on census tracts with historic districts. (See the chart below for the relationships between these variables.)

First, they find that census tracts with historic district designations from 1990–2000 did indeed see a larger increase in male UPSSHs between 2000 and 2010 than tracts without these districts.

They also find that tracts that already had high percentages of male UPSSHs in 2000 but no historic districts were then more likely to establish such a district between 2000 and 2010.

Lastly, the authors find that census tracts with existing historic districts and a larger relative presence of UPSSHs are related to a decrease in non-White and median-income households from 2000 to 2010.

Figure 1: Diagram of significant relationships between historic districts, unmarried partnered same-sex households, race/ethnicity, and income. Note: White background = presence; black background = change; solid line = positive association; dashed line = negative association.

Planners Urged to Address Gentrification Effects

With these findings, the authors make several suggestions for planners and preservationists. The first is to more actively incorporate the LGBTQ histories of historic districts into their narratives, given that this significant story is often left out. Given the relationship between these districts and decreasing rates of Black, Hispanic, and low-income households, planners should also more actively consider the negative outcomes of historic district status, and how a neighborhood trait like housing affordability could be as worthy of protection as architectural merit.

As a queer planning student aiming to work in LGBTQ community development, I find this work significant for providing further evidence not only to common observations that gay men have engaged in neighborhood revitalization through historic preservation but also to concerns that this process often pushes out low- and middle-income communities of color.

As we consider what LGBTQ neighborhood and community development look like in the coming decades, with concerns raised about the “death of the gayborhood,” it encourages us to actively examine who common modes of LGBTQ neighborhood development may be at the expense of, and how we can encourage LGBTQ spaces more inclusive of difference in race and gender identity.

Top image: Near Scott Circle, Washington, D.C. Photo by Flickr user Ted Eytan (CC BY-SA 2.0).