Uncovering JAPA

Big, Open Data Offers New Tools for Transit-Oriented Development

As big and open data becomes more accessible, planners have new tools to revalidate or reexamine existing planning principles concerning transit-oriented development.

These are the takeaways from Jiangping Zhou, Yuling Yang, and Chris Webster's article "Using Big and Open Data to Analyze Transit-Oriented Development" in the Journal of the American Planning Association (Vol. 86, No. 3).

Big Data Examines Transit-oriented Development

Transit-oriented development (TOD) is a widely used urban planning and design strategy to integrate transit services and land use in areas around transit stations. In their study, Zhou, Yang, and Webster use big and open data (BOD) to examine two types of variables common to TOD studies: attributes and outcomes.

The study questions whether and how much TOD attributes contribute to TOD outcomes across metro station areas in Shenzhen, China.

In this case, attributes refer to measurable or perceivable qualities of the TOD, such as density, diversity, and design. In contrast, outcomes refer to measures such as stability and growth in transit ridership or increased transit use.

The authors argue that using big and open data to assess transit-oriented development is useful because traditional data sources have severe limitations and cannot include many station areas without significant effort.

BOD can accomplish this more efficiently and allows planners to develop new metrics to quantify attributes, outcomes, and relationships between the two. For example, planners can use smart card data to get transit ridership data. Apps like Google Maps and Walk Score can provide additional insight to quantify more TOD attributes across an entire city.

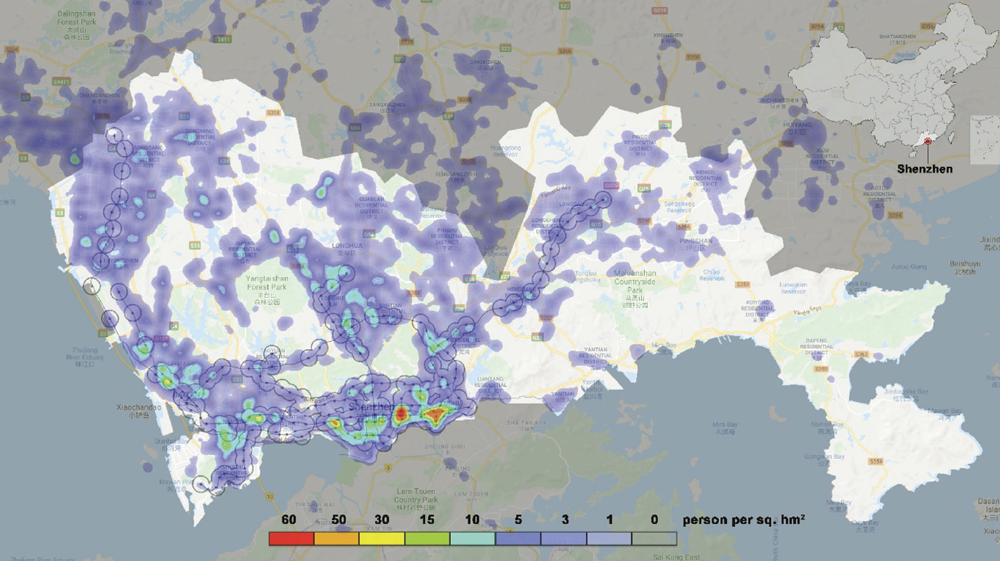

A sample of Baidu heat maps for Shenzhen.

BOD Refines Insights on TOD Effectiveness

While most published studies conclude that TOD attributes bring about at least some TOD outcomes, BOD can draw more nuanced conclusions by referencing these new metrics. As one example, the authors concluded that regional (metro) accessibility had the most significant positive impact on metro ridership in Shenzhen. To elaborate, the distance to a central business district from a transit station and the employment size of the central business district both had significant positive impacts on outgoing ridership at a station.

Of course, there are some drawbacks to relying on big and open data.

It can be expensive to acquire and process BOD. It may also provide only a partial picture and may not represent the population as a whole.

For example, smartphone data overlooks transit users who do not own a smartphone. Finally, there are ongoing questions and challenges surrounding cyber security and privacy. Many transit users do not want their information collected, even if used for universally beneficial planning purposes.

If planners can obtain and use BOD in responsible and ethical ways, there are many lessons we can take away from this specific case study of Shenzhen. But broadly, the authors conclude that planners may consider using BOD as a supplement to and even a replacement for traditional data to measure TOD attributes and outcomes.

As BOD becomes more prevalent and accessible, there is an opportunity to establish real-time performance monitoring systems and tools to collect data for large networks such as all metro stations in a city. With this knowledge, we can implement more informed policies and create better designs for transit-oriented developments in many contexts worldwide.

Top image: Getty Images illustration.