Planning March 2019

Smart Cities or Surveillance Cities?

The terrain is shifting for this movement, as many of us wonder aloud whether the urban tech utopia is all it’s cracked up to be.

By Brian Barth

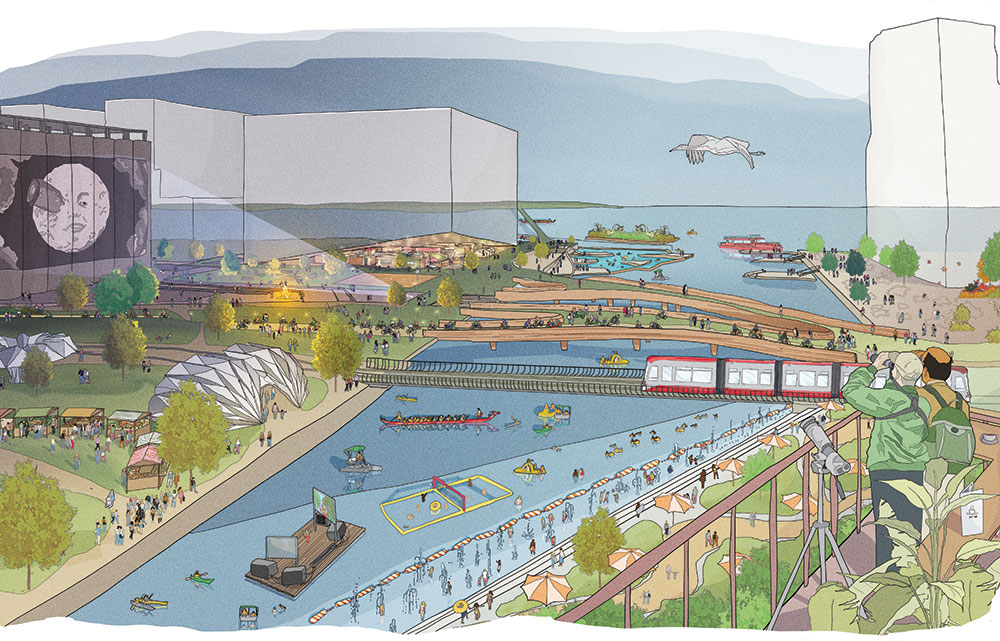

In March 2017, Waterfront Toronto, a public corporation charged with redeveloping 2,000 acres along the city's downtown waterfront, issued an RFP for a "funding and innovation partner" to plan and build a "smart" neighborhood on 12 of those acres, an area known as Quayside. In October that year, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau announced the winning respondent: Sidewalk Labs, the Google sister company focused on urban innovation, which pledged $50 million to devise a plan for a new community "built from the internet up." At the press conference it was revealed that the project may expand to an adjacent 800 acres of former industrial land, some of the most valuable real estate in North America, making this the world's most ambitious smart city project to date.

Sidewalk Labs' proposal sounded great: a district-scale renewable energy system; environmentally conscious wood buildings; driverless buses; underground tunnels roamed by robots, keeping package delivery and waste collection off the public way. Streets would be paved with modular hexagonal pavers, able to be reconfigured for different uses, and embedded with programmable LED lights. And a digital identity system would allow residents to access an array of public and private services.

Urban development-wise, their plan would seem to reflect all the best practices, and then some. But it's not Sidewalk Labs' plans for green-space, buildings, roads, and other conventional infrastructure that have become contentious. Privacy advocates, resident groups, and recently resigned members of the project team have pushed a narrative that Sidewalk Labs' proposed smart city really amounts to a surveillance city, intended to commercialize personal data collected in public space, in the same way that Google commercializes data from our internet searches (ads — custom-tailored according to each person's online activity — account for about 85 percent of Google's revenue).

The smart city industry rests on a foundation of mass-scale data collection — data that can help make cities more efficient, safer, and higher functioning, while also supporting emerging technologies such as autonomous vehicles. But that data is also potentially lucrative in the hands of Big Tech. Among seemingly innocuous technologies, like sensors that collect fine-grained data on local weather, pollution patterns, and traffic, the broad smart city vision encompasses sensors with the ability to collect data from the phone in your pocket or use artificial intelligence-enhanced microphones and cameras to gather intel as you move through public spaces — with no privacy agreement allowing you to opt out and decline service like you can in the virtual world. Further, critics point out that governments often lack the technical expertise, much less policy frameworks, to avoid unintended negative consequences.

Rendering of Sidewalk Labs' vision for the smart neighborhood of Quayside, a 2,000-acre parcel on Toronto's waterfront. Rendering courtesy Sidewalk Toronto.

Sidewalk Labs' Commitment to Privacy

In a recent session on digital governance, Sidewalk Toronto presented a model for data and privacy. "The purpose for urban data collection in Sidewalk Toronto is to improve the day-to-day operation of the neighbourhood and to ultimately create a place that's more sustainable, accessible, and responsive to local needs. In addition to the protections provided by Canadian privacy and other laws, Sidewalk Labs commits to four key components of Digital Governance."

1. Civic Data Trust

Create an independent entity that would establish rules and standards that apply to all entities operating in Quayside, including Sidewalk Labs.

2. Published Standards

Sidewalk Labs will base its technology on published standards, making it easy for others to build and connect new services, offer competitive alternatives, and drive innovation.

3. Responsible Data Impact Assessment

Sidewalk Labs recommends that RDIAs be auditable and, if required by the Civic Data Trust, publicly accessible, absent confidential and proprietary information.

4. Responsible Data Use Guidelines

A commitment to adhere to guidelines that put personal privacy and the public good first, while fostering innovation.

Both local and international media picked up on the surveillance city theme in Toronto, creating a massive PR crisis for Sidewalk Labs and Waterfront Toronto just as they began the planning process. Even Jim Balsille, the cofounder of BlackBerry (the Ontario-based company that dominated the early days of the smartphone market) weighed in, accusing municipal leaders in an op-ed in The Globe and Mailof handing over a large swath of the city to a tech monopoly "whose business model is built exclusively on the principle of mass surveillance."

In October 2018, a year into the project, Ann Cavoukian, the former privacy commissioner of Ontario who was on Sidewalk Labs' payroll as a consultant, resigned, saying she'd been misled about the company's intentions. Her departure was preceded by a parade of other high-profile resignations in response to the project. And in December, the province fired three directors at Waterfront Toronto following a damning report by the Ontario Auditor General, which questioned whether the agency's arrangement with Sidewalk Labs was in the public interest and suggested that government officials may have acted in a conflict of interest by providing Sidewalk Labs with preferential treatment during the RFP process.

All this has shifted the terrain of the smart city movement, which previously had been full of optimism, with cities around the world competing to be seen as the most tech-savvy. CityLab.com declared 2018 the Year of the Smart City Skeptic and christened Bianca Wylie, the Toronto activist leading the resistance against Sidewalk Labs, the "Jane Jacobs of smart cities."

Smart cities take planning

Planners have played an important role in the emergence of smart cities. In 2015, APA's Smart Cities and Sustainability Task Force released a report addressing how technological advances are changing the field of planning and our communities. That work continues, as planners across North America collaborate on how planning can harness or influence the use of smart city technologies in our communities.

In Chicago, Array of Things nodes are attached to 200 utility poles. Data from the network of sensors, including weather instruments, pollution measurement equipment, cameras, and microphones, is available to researchers and businesses. Photo courtesy Argonne National Laboratory.

Pamela Robinson, a professor at the Ryerson School of Urban and Regional Planning in Toronto, thinks planners can take an even more prominent role. She is currently at work on a pair of research projects related to smart city development. "There are many good precedents in infrastructure planning that need to be applied to the use of technology in cities," says Robinson, pointing out the use of environmental assessments as an example. "One of the questions that I'm working on answering is, 'What's the smart city equivalent of that?' Because right now, at least as far as I can see, we don't have one."

Smart city projects tend to be run out of a mayor's office, as flashy pet projects often are, or are tucked away in the chief technology officer's domain or the department of economic development. But as the Sidewalk Labs controversy has demonstrated, it can't be assumed that the public will automatically buy into anything with the word "smart" in it. Which is where planners, with their unique role as a liaison between residents, policy makers, and bureaucrats, come in. Eliciting public input, and properly framing the roll-out of smart city projects in the context of community needs, could go a long way toward establishing the social license to integrate technological innovations within the urban fabric.

Part of the problem in Toronto is a perception, accurate or not, that Sidewalk Labs holds the reins in the planning process, not Waterfront Toronto, creating the impression that the company will proceed according to its own profit-oriented agenda, rather than the community's.

In Kansas City, dog houses designed by Dogspot, a tech startup, are outfitted with cameras and temperature controls. People can leave pets in the secure kennels while they run quick errands. Photo by Barrette Emke for The New York Times.

"The most important thing a municipal planner and a municipal government can do is to have a clear sense of what are their priorities and what they want to accomplish, because that gives you a filter through which you can start to consider the role technology and data will play," says Robinson. "It's much different than a vendor coming in and saying, 'we have this cool technology that can solve X problem.' Planners are well positioned to ask those kinds of questions so that projects can proceed in the public interest."

There's no textbook yet for the role of planners in smart city development, but there may be soon. Georgia Tech professor Jennifer Clark's book, Uneven Innovation: The Work of Smart Cities, due out this summer, will offer a number of policy recommendations for cities, while unpacking the topic through an equity lens. "Who benefits from smart city development and who is left behind?" is a question too often overlooked, in her view.

"The deployment of these testbed sites and technologies is not evenly distributed," says Clark, a planner whose research focuses on the intersection of economic geography and public policy. "When you think about this in terms of what New York has that Peoria doesn't, you see rich people continuing to get rich, right? Assets accrue to assets. Planners are the people who look at the spatial distribution of things, so there's clearly a question of how are we going to think about that and what are we going to bring to the table?"

Clark, who testified in March 2017 at a hearing on smart cities convened by the U.S. House Energy and Commerce Committee, recognizes that new urban technologies must be tested on a limited geographic scale before being rolled out to the population at large. But she encourages cities to think critically about which communities could most benefit from technological solutions. And she cautions them against giving up their citizens' data too readily, not just out of privacy concerns, but because it has economic value to the community that could, within an appropriate ethical framework, be captured.

"Cities are typically offered these technologies through some sort of negotiation with a private firm, whether as an enhancement to an existing service or as infrastructure to provide some new service that the city otherwise would have difficulty finding the revenues to implement," says Clark. "Because cities are very concerned about being left behind, they often perceive themselves to have less leverage in those negotiations than the firm. So they essentially say, 'great, you guys can extract data if we get this infrastructure for free.' No city that I know of has thought really seriously about the value [that they are giving up]."

Clark is working to put some of her ideas into practice as director of Georgia Tech's Center for Urban Innovation and as the associate director of the school's Smart Cities and Inclusive Innovation initiative. The latter provides funding and technical expertise to support smart city projects in small cities and underprivileged communities throughout the state. These include a feasibility study for using shared autonomous vehicles to address first- and last-mile mobility needs in Chamblee, Georgia, and a network of sensors to monitor storm surge and flood risk in real time to improve emergency response in Savannah.

These are small projects, she says, but useful for teasing out exactly what types of data are needed for a given technological solution to succeed, how best to handle privacy for any data collected, and how to make it all financially feasible. Clark suggests that smart city development will be most successful if it's thought of less as a public-private partnership, and more as a series of "public-led projects that have private partners ... this is about the future of how public services and public infrastructure is provided. The privatization issue should be front and center, but I'm afraid it really hasn't been."

COLUMBUS, OHIO: Prenatal Trip Assistance — In November Columbus voted to fund a ride-sharing app (developed pro bono in 2016 by Sidewalk Labs) for low-income mothers. The pilot program, a collaboration between CelebrateOne and Smart Columbus, will help pregnant women reach prenatal appointments, supporting access to health care throughout pregnancy and following birth. The pilot targets women in eight Columbus neighborhoods where the infant mortality rate is highest. Photo courtesy CelebrateOne.

Rising to the challenge?

Smart city development across North America remains limited, and piecemeal, at least compared to the grand visions promulgated by companies like Sidewalk Labs, but every municipality of any size seems to have at least one project in the works. And it's not just Toronto where local governments are learning the hard way that tech for tech's sake is not a winning formula.

One of the most high-profile projects in the U.S. is in Columbus, Ohio, the winner of the U.S. Department of Transportation's Smart City Challenge in 2016. Since then, the city has leveraged its $50 million award into a $500 million investment pool, though it has realized just one project: a six-person autonomous shuttle circulating tourists through downtown sites. This came as a surprise to some local social advocates.

In selecting Columbus, DOT officials noted they were particularly impressed with the city's stated priority to use technology, and the agency's funding, to address maternal health issues and the sky-high infant mortality rate in the deeply impoverished South Linden neighborhood. The idea was to develop a subsidized system where moms in need could send a text message to summon a van or a ride-hailing service when they needed a lift to a health care provider, along with a range of other tech-enabled mobility interventions.

But in late 2017, news broke that the original plan to help some of South Linden's most vulnerable residents had slipped off Columbus's smart city agenda in favor of flashier projects in other parts of town. Facing a backlash, officials quickly renewed their pledge to South Linden: This summer, Columbus will launch a pilot program to provide at-risk mothers with on-demand transportation.

Amber Woodburn McNair, a planning professor at Ohio State University who participated in a working group to help establish the Smart Columbus Operating System (a web platform intended as a hub to integrate data from various smart city initiatives as they are rolled out), observed what she considers a significant disconnect between the technologists working on the project and the sort of public engagement process that she is familiar with as a planner.

"They just sort of showed up at meetings in South Linden like, 'hey, we're going to bring you driverless cars and smart things.' And the residents were like, 'well, I really just need to get to my job and get my kids to health care' — really practical things," says McNair. "Tech enthusiasts have so much excitement and energy to bring these solutions, but I think they don't always fully grasp the problems. At least now they're trying to reflect and alter course in meaningful ways here in Columbus, but I still haven't seen the involvement of the right disciplines to guide that effort in a respectful and qualified way."

Jason Reece, another OSU planning professor who has worked extensively with the South Linden community and whose research on the infant mortality issue helped to inform Columbus's smart city grant application, draws a connection between the surveillance aspects of smart cities and the challenge of engaging vulnerable communities.

"In communities where people feel under intense surveillance by law enforcement all the time, there is a hesitancy to engage with new technologies that involve tracking you, even if they might be helpful to you," he says.

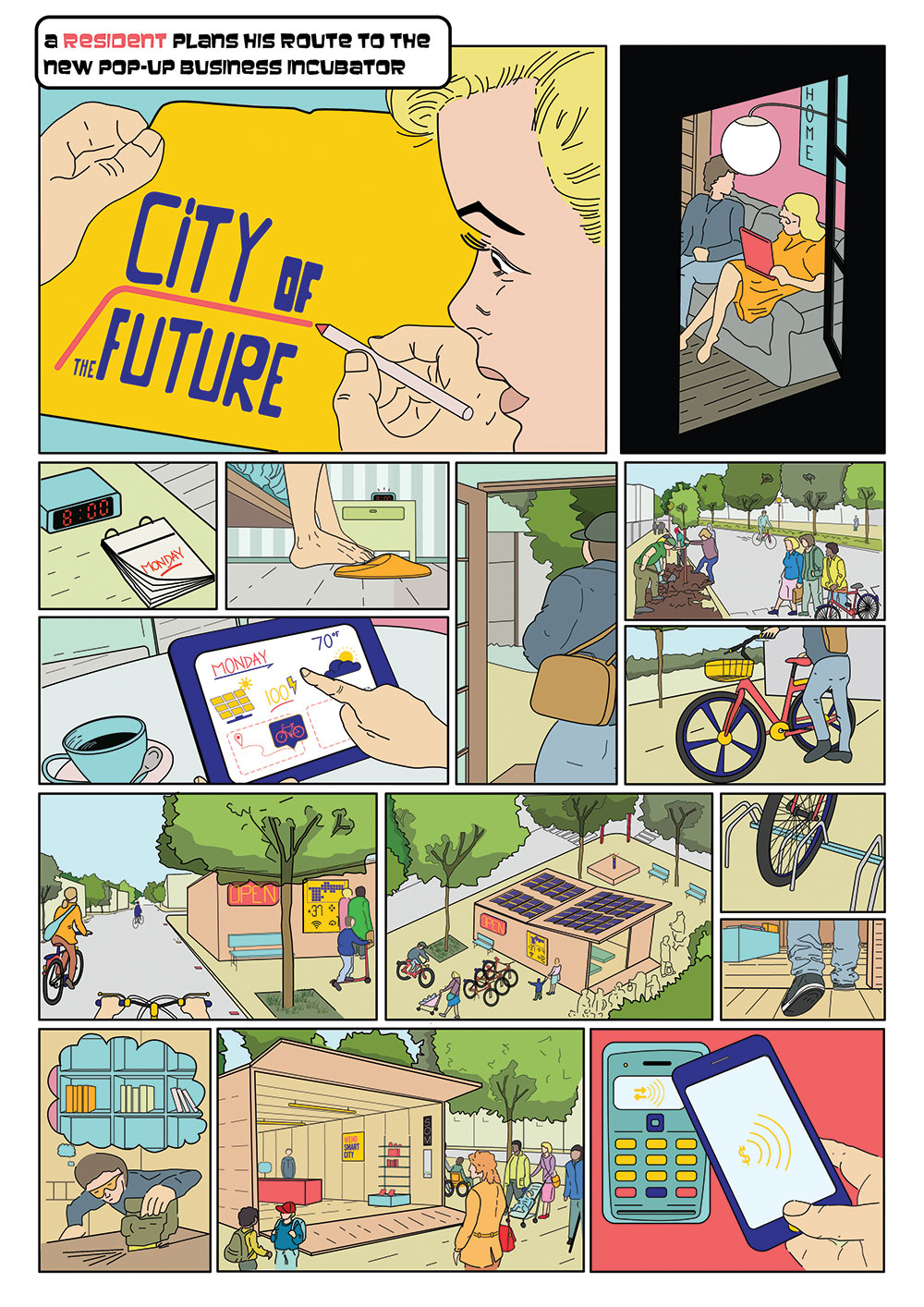

WEST HOLLYWOOD: California Smart City Strategic Plan — A page from a graphic novel developed for the city of West Hollywood explains how technology can facilitate a seamless mobility experience in West Hollywood through better information, connectivity between public and private transport modes, and payment options. The overall experience is further enhanced by smart urban design and safer streets as well as a pop-up business incubator space for entrepreneurs. As WeHo Smart City integrates better data management and decision making in a smart city hall, there is greater potential to introduce these services for a "right-sized" experience tailored to the individual needs.

People-first policy

Few people have as much experience with the practical aspects of planning smart city projects as Ashley Hand, who has served as Los Angeles's transportation technology strategist and as the first chief innovation officer for Kansas City, which has been widely hailed as an early adopter of the smart city concept. Most recently, Hands cofounded CityFi, a firm focused on "urban change management" and "people-centric" smart city solutions, which promises to help local governments "separate the techno-optimist hype from the real game changers."

CityFi has consulted on smart city projects throughout the world, from Kansas City to Kazakhstan, Seattle to Singapore. Hand says she's brushed up against the challenges of privacy and equity time and again, as well as the more basic problem of explaining to the public what a smart city is and why they should care.

Recently, while working on a smart city strategic plan for West Hollywood, California, she landed on a new idea to address the issue of public engagement and perception. In addition to all the customary planning documents, she commissioned a "graphic novel" — essentially a series of comic strips that tell the story in a way the average resident might relate to.

"It was great to help people understand, from a boots-on-the-ground perspective, what the implications of a smart city are for them, whether they're a resident, a business owner, or perhaps a visitor," says Hand.

She acknowledges that it's somewhat natural for citizens to have an Orwellian reaction upon realizing how much data is now being collected, or could be soon, about their every movement. Which is why she thinks it's important to encourage public discourse about it: Residents might embrace certain types of data collection if they understood how it benefits them, while having the opportunity to decide what is off-limits through a democratic process.

"There are trade-offs between personal privacy and the social benefits that, hopefully, can come through these technologies, so we really need to think carefully about the rights we're giving up. We have to figure out how do to define what those trade-offs will be and where to draw the line."

It's a conversation that's slowly beginning to happen. Chicago's Array of Things — a network of sensors, including weather instruments, pollution measurement equipment, cameras, and microphones, now attached to about 200 utility poles throughout the city — provides an example of how a smart city project can move from skepticism to acceptance.

When it was first announced, the public got wind that sensors identifying resident's smartphones were possibly going to be included. That idea was quickly dropped amid a fairly hostile reaction. An outreach campaign was launched to clarify that the microphones, for example, were designed to measure street noise, not record conversations. The cameras were for counting pedestrian traffic and would not be equipped with facial recognition technology; images would be processed within each unit and then deleted, so that only raw, aggregate data would be transmitted to project servers.

Perhaps most importantly, data was to be held by the Argonne National Laboratory, not a corporation, with an independent panel of privacy experts overseeing how it was managed. Now more than two years into the project, Array of Things data is freely accessible to researchers, businesses, and social advocacy groups, and the project is expected to expand to 500 data collection sites in 2019.

New York City, Barcelona, and Amsterdam are on a similar mission to put people at the forefront of the smart city conversation. In November 2018, the three cities joined together to form the Cities Coalition for Digital Rights in an effort to set a high bar for what human rights look like in a smart city context. Amsterdam, for example, is considering a ban on wifi tracking and adopting an approach of collecting the least data possible for a given purpose, while requiring that privacy standards be baked into the design of technology implemented in public space. Barcelona has created an Ethical Digital Standards Policy Toolkit, which it is encouraging other cities to adopt.

Hand points to the advent of the automobile age in the early 20th century as an analogy for reckoning with how technology may again catalyze massive shifts in urban life, not all of them for the better. "With cars, we made some really serious generational decisions that ended up making it more difficult for people to get around through active modes of transportation. We have an opportunity now to think ahead of current technology to ensure it enables desired outcomes and isn't just a shiny object that leaves us with unintended consequences. Technology is shaping our cities whether we like it or not, so it's really important that we begin to have a conversation about this new social contract."

Brian Barth is a freelance journalist with a background in urban planning. He lives in Toronto.