Planning April 2020

Primed for Deliveries

Rapidly changing e-commerce trends and technologies mean big changes for land-use and infrastructure planning.

A Note from the Editor

If e-commerce has always been fast-moving and ever-changing, never has that been more clear than during the COVID-19 pandemic.

With people staying at home all day, most stores and businesses temporarily shuttered, and restaurants closed to dine-in patrons, many Americans are turning to e-commerce and contactless delivery for groceries and other goods, including those who have not typically been online shoppers.

Figures on online sales are hard to come by in these early days, and what the long-term impacts will be on the economy, the built environment, and consumer behaviors is impossible to say. But Planning magazine talked to this article's author, Lisa Nisenson, in late March, and she offered some food for thought.

Nisenson has noted some trends accelerating and shifting already, with more to come. Look for small autonomous vehicles, like deliverybots, being used for totally contactless deliveries, aerial drones dropping medical and other supplies — especially in suburban and rural areas — and even robots designed for e-commerce being redirected toward patient care, like taking temperatures and delivering meals, or sanitizing transit vehicles.

For planners and local governments, the author offers a few pieces of advice.

First, when it comes to permitting new technologies during the pandemic, be careful to make those permits time-limited or associated specifically with an emergency declaration, so that you can make thoughtful decisions that carefully consider long-term impacts later.

Second, be alert to how citizens' views toward privacy might shift. Overseas, closely monitoring people infected with or who have recovered from COVID-19 has helped to control the spread. If that becomes widespread in the U.S., that raises questions about data collection and security, smart cities technologies, and more.

Finally, Nisenson says that local governments will be looking for new revenue streams, to offset losses related to the pandemic. E-commerce technologies may open up some new ideas, including local governments leasing space (or airspace) in the public way for autonomous vehicles, if state law allows.

Listen to the full interview with Lisa Nisenson:

By Lisa Nisenson

Once regarded primarily as a segment of transportation, freight and deliveries are increasingly commanding attention from a wider range of planners, government officials, and policy makers. The rapid rise in e-commerce deliveries and online food and grocery orders is driving many cities to develop a range of strategies to control curbside congestion. E-commerce impacts, however, extend far beyond the curb.

As stores race to reduce order fulfillment time, consumers expect quicker and quicker turnarounds. Over the past six years, Amazon has been quietly working toward a goal of delivering online product orders within 30 minutes.

A delivery driver organizes a variety of e-commerce orders — ranging from food kits to pet supplies — on a New York City sidewalk. Photo by Ablokhin/iStock Editorial/Getty Images Plus.

That goal won't be realized by increasing the speed of warehouse workers and delivery trucks. Instead, retailers like Amazon envision an entirely new supply chain powered by state-of-the-art technologies and automated delivery systems. Transportation technology companies are responding to the opportunity with new product lines like automated delivery vans, delivery robots, and aerial delivery drones.

Early technology pilot programs provide a glimpse into this delivery future. Starship Technologies and George Mason University sponsored a pilot of 25 delivery robots on an 800-acre Virginia campus. After collecting two months of data, researchers found a surprising trend: an uptick in students ordering breakfast. 1

1. Deliverybots (click to expand)

Starship Enterprise photo taken at Northern Arizona University.

In December 2019, Plus.ai completed the first coast-to-coast freight run in an autonomous truck to deliver butter. 2

2. Self-Driving Coast to Coast

Photo courtesy Plus.ai.

In October 2019, UPS gained regulatory approval for commercial drone deliveries after a successful pilot with Wake Medical Center in North Carolina flying blood samples. 3

3. Delivery Drones

Before it started working with UPS, WakeMed Health used couriers to carry blood samples from its hospital to its main lab. But UPS and WakeMed were able to cut down delivery time to between five and 10 minutes with a Matternet drone carrying the samples. The drone flies along a predetermined route to a fixed landing pad at the hospital.

And in February, the U.S. Department of Transportation approved a regulatory exemption that allows Nuro, an autonomous delivery vehicle manufacturer, to begin public road testing and to prepare for deliveries to customers' homes.

For many retailers and customers, these advancements can't happen quickly enough. But the fanfare surrounding delivery pilot projects overlooks an important success factor: disruptive new technologies, deployed at scale, will require fundamental shifts in how communities and regions manage land uses and infrastructure.

Changes ahead

Traditionally, a local planner's role in commerce and freight has involved reviewing warehouse zoning, traffic patterns, and loading in public rights-of-way. At a more granular level, responsibilities have included loading zone design, local circulation, and signage that specifies delivery hours. For curbside congestion, planners collaborate with parking enforcement and the business community to assess and enact solutions.

Over the past 20 years, planners have worked with small retailers and downtown districts to help them compete with big box retailers and online merchants. Those same big box retailers are now having to address competition from online businesses, both externally with competitors and internally with their own online services. A good example of a retailer's response is Walmart, which launched Walmart Reimagined to depict potential new uses for empty parking spaces surrounding its stores. 4

4. Parking Lots

Photo courtesy Walmart.

This infill strategy would make Walmart stores a destination by adding dining, event venues, and store pickup of items ordered.

Growth in the e-commerce sector shows no signs of slowing down any time soon. UBS projects that the online share of retail sales in the U.S. will rise to 25 percent (from 16 percent today) by 2026. So it's little wonder stakeholders at the regional, local, and even building scales are increasingly recognizing the need to understand and plan for shifts in freight, logistics, and deliveries.

The most immediate implications for planners fall within the interplay of vehicle technology, warehouse and distribution infrastructure, and traffic impacts — along with some wildcards that could be coming in the near future.

Already the largest internet-based retailer in the U.S., Amazon is moving fulfillment centers closer to consumers and envisions new transportation modes to get the orders to them. Photo by Jillian Cain.

Vehicle technologies

Retailers and shipping companies are experimenting with new delivery vehicle types, from electric bikes and scooters to aerial drones and everything in between.

E-scooters and e-bikes offer compact, electric-assist delivery vehicles that can navigate crowded city streets. UPS has teamed with the Pasadena-based company Urb-E for a small scooter-trailer combination that can haul a 350-pound load and collapse to the size of a carry-on bag. In December 2019, New York City announced a six-month pilot allowing e-cargo bikes to park in commercial delivery zones. 5

5. Cargo Bikes

Photo by Gabby Jones/The New York Times.

The goal is to reduce congestion during peak delivery hours in a city where 1.5 million packages are delivered each day. For planners, e-bikes are far less imposing than larger delivery vans on city streets, although they will still compete for space in curbside transit and bicycle lanes. Because of their smaller capacity, however, e-bikes won't completely replace larger delivery vans and trucks.

Automated delivery modes introduce additional layers of complexity. In addition to working with information technology colleagues on data and digital security measures, planners will need to work with roadway designers and public works departments to consider infrastructure changes needed to support automated vehicle movement and navigation. Some of the core technologies such as cameras, sensors, and radar for reading the road will be located on or within the vehicles, but supporting infrastructure outside the vehicles will be needed, including roadside sensors that communicate alerts to vehicles, machine-readable signs, and lane markings.

Operationally, each automated vehicle type comes with its own set of benefits, concerns, and requirements. For example, zero-occupancy vehicles like Nuro's R2 will take up road space, traveling at low speeds (up to 25 mph). 6

6. Self-Driving Delivery Vehicle

Photo courtesy Nuro.

While the vehicles are narrower than typical automobiles, they will vie for road space with a growing set of mixed-motorized vehicles.

Aerial drones introduce planning for airspace, a new and largely untested infrastructure layer. Whether drone deliveries in urban areas will be feasible is still a big question on several fronts, particularly pedestrian safety, privacy, interference with emergency response, and noise.

In rural areas, aerial drones show promise in delivering medicine and supplies without roads or when speed is essential. Drones could also lessen deliveries' carbon footprint in suburban areas. Imagine a delivery truck parking once within a large subdivision and using aerial drones to dispatch packages. From a planning perspective, this could usher in new subdivision designs with low-impact flight paths.

For aerial deliveries, planners will need to translate and align layers of federal, state, and local regulations. For instance, local governments often have existing regulations for small unmanned aircraft, such as model planes and drones used now by hobbyists. But with growth in commercial applications, there has been little discussion on what happens when aerial drone delivery expands to multiple companies. It's easy to observe operations during individual small pilots, but more discussion is needed about air traffic scenarios at scale in urban areas.

Deliverybots are also largely untested outside of confined courses and campuses. They pose unique challenges in larger urban settings, where planners are already trying to manage intense competition for space on sidewalks and along curbsides. (See "Curb Control," June 2019.) Cities are raising concerns on crowding and how audible alerts will affect other sidewalk users' experience. In November 2019, New York City issued a cease-and-desist letter to FedEx for an unannounced demonstration of its sidewalk delivery bots. The city's letter cited several violations of vehicle and traffic laws, including that motor vehicles are prohibited on sidewalks unless granted a special exemption and registration.

Also at issue is the fact that wheeled deliverybots typically cannot solve the last 50 feet problem of accessing a porch or doorstep. As such, companies are working on stair-climbing models 7 and delivery droids with articulated appendages.

7. Stair-Climbing Deliverybots

Courtesy FedEx.

Warehousing and distribution

Once relegated to remote industrial parks, warehousing is rapidly changing as e-commerce fulfillment companies seek locations closer to consumers. This reversal is challenging how planners, companies, and real estate investors define "highest and best" use, particularly in urban areas.

As one example, Amazon is buying and demolishing malls, 8 converting space from retail use to warehousing and distribution.

8. Mall Impacts

Photo by Nicholas Eckhart.

Cities and suburbs often identify many of these sites for mixed-use redevelopment and employment centers. But to get ahead of this potentially unwanted trend and prevent warehouses locating where they were never intended, cities should quickly review and reinforce mixed-use zoning and planning requirements or investigate new codes and overlay districts to manage warehouse locations and supporting infrastructure.

A second code-related issue relates to e-commerce trends affecting existing retailers. According to Target's CEO Brian Cornell, delivering an online order from an existing store rather than a regional warehouse cuts cost by 40 percent. Handling costs are further reduced when customers "buy online pick up in store" (or BOPIS).

With the lines among retail outlet, warehouse, and distribution hub blurring, it's time for planners to revisit traditional assumptions on trip generation, parking, and circulation. In 2018, the Federal Highway Administration studied the rapid and interlinked changes associated with e-commerce, freight, and land use as they relate to travel demand modeling. While the implications for planning are still unfolding, planners can expect changes to rigid use categories and associated trip generation rates.

Grocers are also reinventing store spaces to meet increasing demand for both grocery deliveries and in-store order pick-up. According to Rick Stein, AICP, principal of the Urban Decision Group and recent Zoning Practice author, grocery and general merchandise stores can be easily rearranged to dedicate less space to aisles and more space to storage. Companies are using technology combinations to help rekey their business models. "There are automated fulfillment systems — like Ocado, which is used by Kroger — that could be fit into the reconfigured space. When coupled with [autonomous delivery services like] Nuro and online ordering, companies can effectively automate the entire fulfillment process," Stein says. Site plans built around peak shopping hours, limited freight deliveries, and the number of warehouse workers no longer represent the new era of fulfillment.

The research firm Capgemini identified four designs grocers are using to fulfill two-hour and same-day deliveries. 9

9. Delivery Window

Photo by Krblokhin/iStock Editorial/Getty Images Plus.

Most are alterations to traditional building formats; however, there is a new category of "dark stores" to hasten fulfillment. Dark stores are physical storefronts that have essentially the same layout as the retail outlet, but they are only open to staff who are fulfilling online orders, not the public. While these stores contribute to the local economy, they do little for the street life often associated with street-facing grocery stores. Nico Larco, professor and director of the University of Oregon's Urbanism Next Center, refers to the proliferation of small distribution hubs like these as the atomization of fulfillment services, as retailers seek to spread multiple locations closer to customers.

Third, planners should pay attention to reuse of existing structures for warehousing. New third-party logistics companies that handle distribution for multiple companies are seeking out urban and suburban spaces like abandoned mills and parking structures that facilitate large automated fulfillment equipment. For example, the real estate management firm JLL is converting spaces in the underground Millennium Parking Garage in Chicago into an urban fulfillment center.

Forecasting, planning, and site design are ripe for better modeling and architectural innovation. Planners have an important role to play to ensure the placement of logistics hubs and the decisions around how those deliveries are made align with transportation, economic, and sustainability goals.

London provides a cautionary tale. While the city's renowned congestion charge has reduced single car use from 50 to 37 percent since 2003, delivery van trips increased 25 percent over the past decade, diminishing sought-after congestion relief.

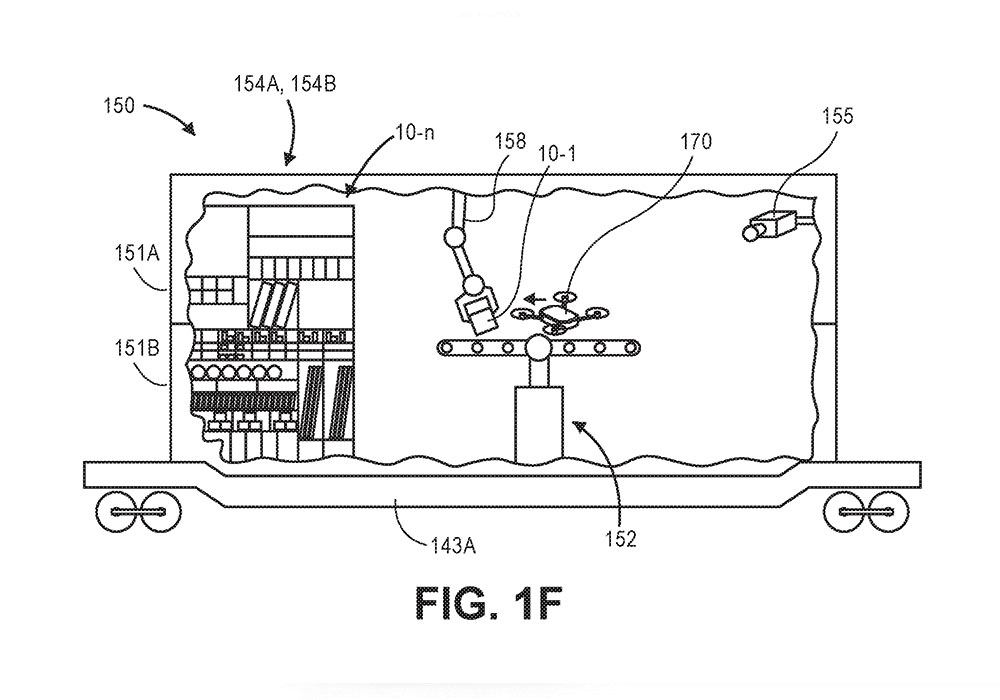

There are also signs that e-commerce outlets are seeking ways to bypass physical distribution centers altogether by exploiting autonomous technologies. Amazon is famously secretive on its expansion plans; however, one can gain clues contained in the company's patent applications. In November 2019, Amazon filed a patent for using intermodal carriers and aerial drones for demand-responsive distribution. 10

10. Amazon Patent

Photo courtesy U.S. Patent and Trademark Office.

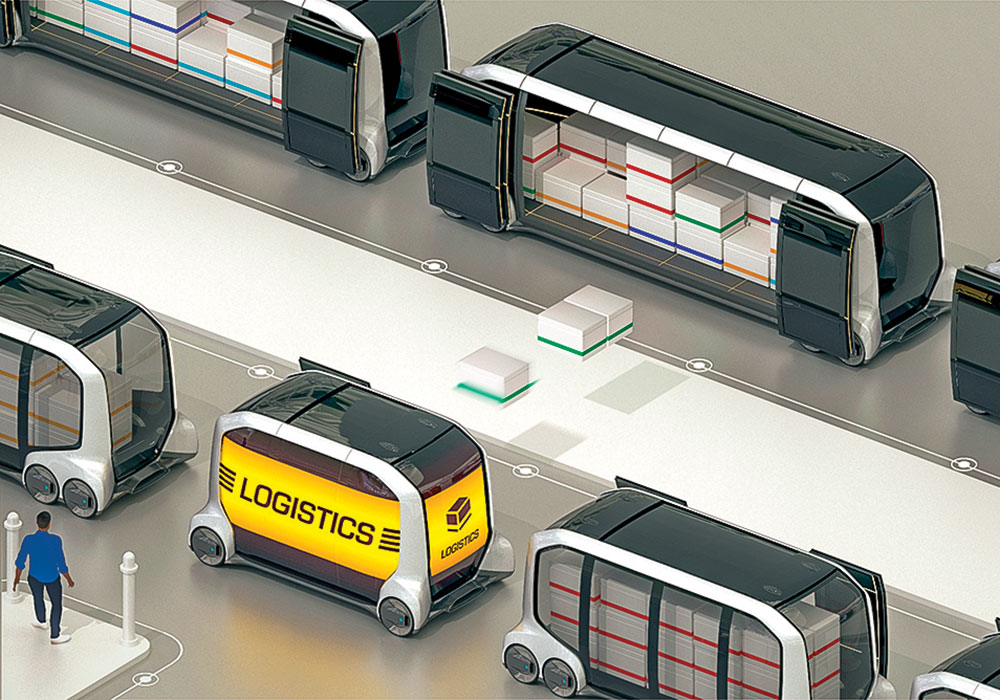

Likewise, Toyota's e-Palette is a reconfigurable shell that can serve as either a mobile showroom or a warehouse.

This technology-enabled shift from land uses (retail and warehousing) to mobile vehicles would have profound implications for localities related to traffic circulation and commercial real estate. According to Rick Stein, it could also get tricky when it comes to local tax bases. "One concern regarding services such as e-Palette 11 or Amazon's Treasure Truck is the exact location of the sale could impact where sales tax is applicable."

11. Multi-Function Vehicles

Photo courtesy Toyota.

Traffic impacts

In the past, travel associated with logistics was segmented into freight, local delivery, and retail traffic, and the last mile of delivery has traditionally been carried out by a shopper or restaurant patron. E-commerce has changed flows in both obvious and subtle ways. The increase in FedEx and UPS trucks is noticeable, particularly in congested urban areas. According to the University of Washington's Freight Lab, Seattle trucks comprise seven percent of vehicles on the road, yet create 28 percent of the congestion.

As e-commerce evolves, traffic modeling will need to consider less obvious changes in package and customer flows. For example, customers can increase convenience and reduce theft risk by retrieving packages through pickup kiosks, package lockers, and even opting for car trunk delivery. 12 What's less clear is how to model and account for these flows.

12. Car Trunk Delivery

Photo courtesy Amazon.

Traffic planners also need to factor in the fact that almost 30 percent of all online orders are returned and almost 15 percent of deliveries fail to make it into customers' hands. Amazon has also partnered with big box Kohl's locations to accept returns, adding to the difficulty of trip assignment. Under this model, an order's journey starts with a delivery trip from Amazon fulfillment to the customer, a retail trip (the customer returning the product) to Kohl's, and a reverse logistics trip (for product reprocessing). It is unlikely Kohl's original traffic impact study foresaw these new patterns.

While these examples describe small individual trip changes, predicted e-commerce considerations for autonomous air and ground drone delivery suggest need for additional research and modeling. The stakes are consequential in localities that assess traffic and mobility fees. Cities may want to revisit formulas to strengthen the nexus between traffic impacts and assessed fees. Likewise, cities need to establish curb priorities. According to Juan Matute, deputy director of the UCLA Institute of Transportation Studies, "What urban planners and the cities they serve need to realize about managing curbs is that apps, data, and micropayments aren't a substitute for prioritizing access for goods and people over vehicle storage. Allocate space accordingly."

Terms and Trends to Watch

AUTONOMOUS VEHICLES: Several vendors are outfitting AVs to serve as delivery vans.

BUY ONLINE PICK UP IN STORE: BOPIS allows customers the ability to order goods online and retrieve at a vendor's brick-and-mortar store.

COURIER NETWORK SERVICES: The ability to order deliveries (typically food and groceries) online or through a mobile app. Companies work with couriers who fulfill orders.

DELIVERY DRONES: Small AVs used to transport packages and food. There are two types: unmanned aerial drones and ground drones. Ground drones are wheeled devices that are also referred to as deliverybots. New nonwheeled versions with articulated limbs can climb stairs.

OMNI-CHANNEL RETAIL: Large retailers with a consistent shopping experience across all channels — brick and mortar and online.

REVERSE LOGISTICS: The process of managing the reverse travel of a product into the supply chain; for example, reprocessing returns.

ROBOTIC DELIVERY: The transport of food and goods using automated robotic devices and small vehicles.

Wild cards

Projections involving any type of emerging technology need to acknowledge the likelihood of unexpected innovation and failure. This is particularly true of freight and logistics, which is at the confluence of several sectors affected by disruptive technologies including vehicles, architecture, manufacturing, and communications.

The first, and perhaps largest, wild card is cybersecurity. With automated vehicles of all types, cyberattacks can be as small as a minor service interruption, or a more serious remotely controlled hijacking. Planners in all sectors should work with their technology officials to develop emergency plans and interventions in the event of an attack. For example, a campus may want to employ scenario planning and contingency plans to proactively plan for a range of cyber and communication disruptions, including connected and autonomous delivery vehicles.

The second wild card is technology's continuous evolution. Today's small air and ground-based delivery robots could be candidates for further disruption, so cities should refrain from regulating singular technologies or design. Similarly, infrastructure is undergoing rapid change to factor in autonomous technologies, sustainable materials, and future funding options.

What's on the horizon for delivery options? Curbsides designed to keep transit and transportation network and delivery vehicles out of travel lanes, retractable pylons to allow flexible uses for curb space, balconies doing double-duty as landing pads for aerial drones, and special bays for deliverybots are all possibilities. Photo courtesy WGI.

Entrepreneurs are also experimenting with underground delivery networks through hyperloops to relieve surface congestion. "For these reasons, investing in expensive infrastructure adaptation projects (sensors, etc.) may be unwise. There's probably already a cheaper solution on the horizon," says Stein.

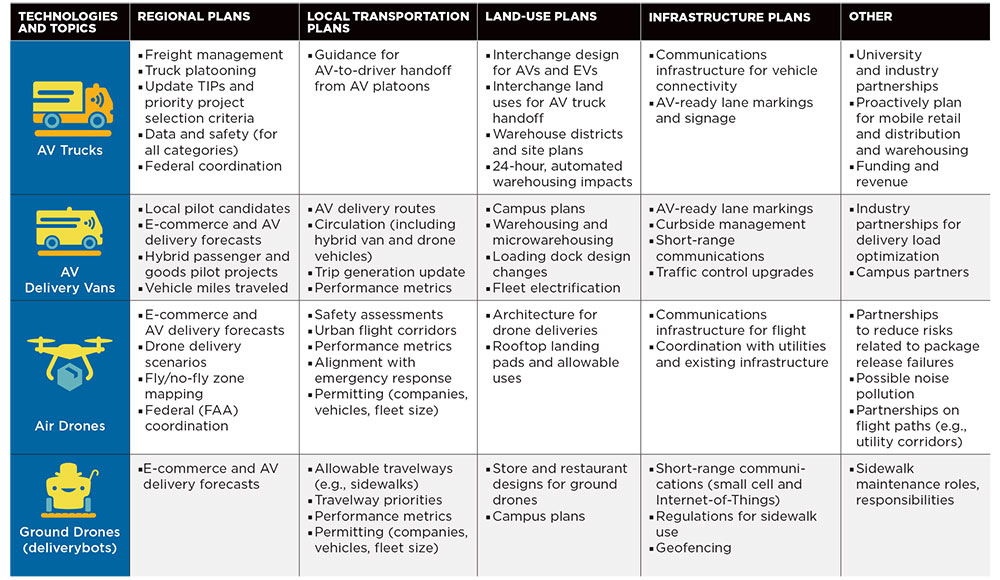

Planning for E-Commerce and New Delivery Options

The future will bring lot of unknowns. Here are several considerations to help tackle today's challenges while anticipating tomorrow's risks and benefits.

What planners can do

Planners everywhere face the dual challenge of addressing today's e-commerce impacts while anticipating the future benefits and risks associated with a slew of emerging technologies. At the local level, planners have several tools to manage risk.

First, knowledge of how to design and execute pilot projects to test new technologies is critical. And stakeholder engagement is important, including populations likely to be impacted, positively and negatively, by e-commerce. For example, expanded delivery options have the potential to benefit mobility-limited populations.

In the near term, communities of all sizes can adopt resolutions that establish expectations on services, stakeholder needs, data, and priorities. Planners should also review plans and use plan updates to integrate e-commerce. In addition to freight and transportation plans, consider how e-commerce fits within plans affecting utilities, economic development, and sustainability. For example, aerial delivery drones are expected to reduce emissions, though greenhouse gas benefits rely on several variables: distance, lift mechanism, weight, and the energy footprint of warehouses.

Multiple warehouses and consolidation centers can reduce distance, but can add to the overall carbon impact once building operations and HVAC systems are factored in.

Planners should also tap into the growing list of American Planning Association resources covering vehicle technologies, retail trends, and e-commerce. Given the fast pace of change, planners can use scenario planning to examine the plausible evolution of both e-commerce and autonomous delivery trends and related impacts, both positive and negative.

Lisa Nisenson is vice president for new mobility and connected communities at WGI, focusing on the intersection of technology, mobility, infrastructure and land use. In her role, she helps communities get in front of and harness innovation and technology within codes, plans, and stakeholder engagement.

Allons-Y! Land-Use Plans for Freight in Paris

Chapelle Internationale Logistics Hotel. Illustration courtesy Sogaris.

By Daniel Haake, AICP, and José Holguín-Veras, PhD

The rise of e-commerce has created challenges for communities across the globe. Trucks delivering packages are often forced to use city streets and park in nondesignated areas — creating congestion, safety issues, impacts to historic buildings, and conflicts with bike and pedestrian facilities that impact the quality of life of our communities. These problems are particularly challenging in a dense, historic place like Paris, as well as the larger region.

In 2006, public- and private-sector partners in the Région Île-de-France undertook a groundbreaking effort to address these challenges. Seven years later, the group released a formal charter that created a list of projects to help solve urban freight issues. Among others, it called for including logistics in the region's master plans. In the following years, the Région Île-de-France (with many partners) created three complementary plans — a regional master plan (2013–2030), a regional transport and mobility plan (2014–2020); and a regional environmental plan (2012–2020) — to coordinate land use, transport, environmental, and logistical issues.

Execution of those plans has proven more difficult. Since the Région Île-de-France has no formal land-use authority, it is up to its 1,281 municipalities to make individual changes to their ordinances to effect coordinated change. A case in point: the plans identified areas to be set aside for strategic freight-related (re)development, but several have already been redeveloped into other nonfreight-related uses, including a large rapid transit initiative called the Grand Paris Express.

Despite this, concepts captured in these land-use plans have found notable success in the city itself.

PARIS LOGISTICS DEVELOPMENT PLAN

L'Atelier Parisien d'Urbanisme (Paris Urbanism Agency) devised a citywide logistics plan that focused on strategically located multimodal logistics terminals, crossdocking terminals (used to shift freight from large trucks to smaller, clean-energy vehicles for last-mile deliveries) and storage lockers for pickups. One such crossdocking facility, for instance, is proposed to be built under the bridges of the Boulevard Périphérique, the major freeway that encircles Paris.

In 2016, Paris passed changes to the zoning ordinance to implement the logistics development plan. Most notably, the city deemed warehouses and crossdocking facilities as "necessary equipment," effectively making them a public use like schools and libraries.

The zoning ordinance specifically designates 60 parcels for future crossdocking facilities, ensuring that the facilities would be included in any redevelopment. Similarly, large existing warehouses in "large urban service zones" were banned from redeveloping into any other use.

CHAPELLE LOGISTICS HOTEL

Paris has implemented a concept known as "logistics hotels" to break down large truck shipments into smaller vehicles powered by clean energy to make final deliveries. In April 2018, the Chapelle Internationale Logistics Hotel opened in an affluent part of the city. The multistory, multiuse facility (which is both under and above ground) services e-commerce companies (like Amazon Prime Now) that use the facility to reduce regional truck movements, to charge smaller electric delivery trucks, and to be closer to their customers. The building is deliberately integrated into the neighborhood, and it's also home to a data center, offices, sports facilities, and an urban farm.

While the region's approach to freight-related land-use decision making remains highly fragmented, Paris has embraced innovative approaches, demonstrating that land-use policy and planning are an important part of the solution to urban freight logistics challenges.

Daniel Haake is a senior transportation planner at HDR and chair of ITE's Urban Goods Movement Standing Committee. José Holguín-Veras is the William H. Hart Professor and director of the VREF Center of Excellence on Sustainable Urban Freight Systems at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute.