Planning February 2020

Engagement

Putting Freedom Colonies on the Map

One planning professor’s mission to document and preserve every Black settlement in Texas.

By Tatiana Walk-Morris

For Andrea Roberts, PhD, assistant professor of urban planning at Texas A&M University, the journey to researching freedom colonies in Texas began in 2014 while attending a heritage and homecoming festival in Shankleville. She watched residents commemorate the Black settlement's founders, work to reinvest in areas they deemed important, and maintain a network with other Black settlements in the region.

A local church hosts a picnic during County Line's 1991 homecoming. The three-day event, which still takes place today, honors the Texas freedom colony's history and residents — past, present, and future. Photo by Richard Orton.

That experience, plus her own family ties to several freedom colonies, led her to found what would become the Texas Freedom Colonies Project, which aims to map every Black settlement established by formerly enslaved African Americans throughout the state between 1866 and the 1930s, from Juneteenth through the end of the Depression. The effort also seeks to connect experts with local communities, provide settlers' descendants with technical assistance, and ultimately bring awareness to the colonies' existence and preservation needs.

"We are really trying to build a comprehensive assessment of African American communities, not only as historic places, but as contemporary places with Black historic pasts," Roberts says. "Our mission is to avoid the sentimentality and memorialization of these communities by bringing them into discourse and research on contemporary planning and sustainability challenges."

Absent much existing data, project founder Andrea Roberts relies on personal interviews to learn about the 557 known freedom colonies in Texas. Photo courtesy Texas Freedom Colonies Project.

Living history

Freedom colonies — also known as freedmen's towns, or Black settlements, towns, or enclaves — are largely absent from local maps, census data, and mainstream history, often because they lacked what are viewed as typical markers like a city hall or stores.

"Some of it is definitional, which make it what's called structural racism, because it's part of the ways in which we conceptualize space and citizenship," Roberts says.

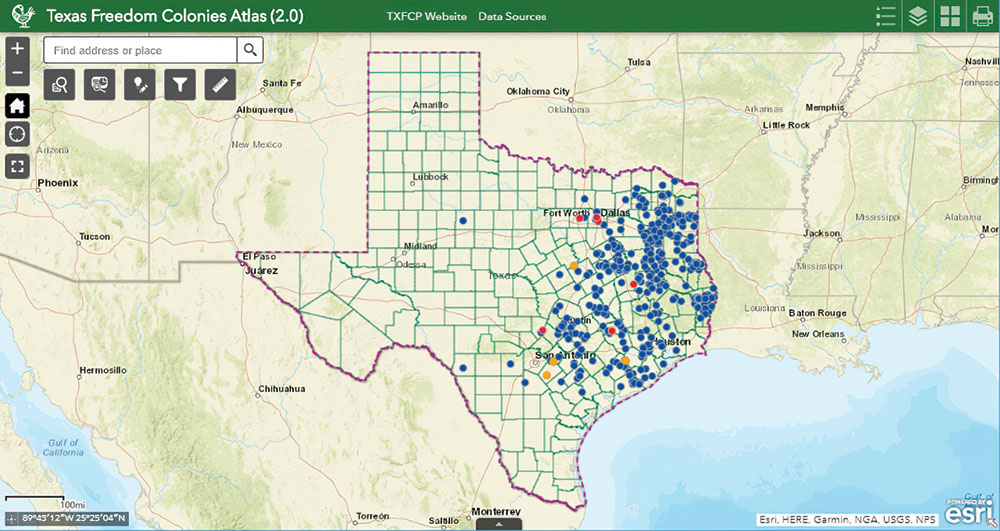

In part, the Texas Freedom Colonies Project creates space for people to rethink their criteria for what make a place, she says, and allow for local definitions. It aims to map the 557 known settlements and add any missing locations. So far, 357 settlement areas have been captured in an online atlas, and 36 crowd-sourced settlements have been entered by the public. About 200 other locations need to be verified so that they can be added to the map, she says, and there may be many more colonies they aren't even aware of yet.

Data collection is a serious challenge in many cases, as the settlements' populations have changed significantly over time. Black-owned lands were often taken via auctions, partition sales, and theft, she says. As a result, some areas have lost all traces of the colonies that once existed there, and others may have only a cemetery, a church, or a handful or residents left. The project has required some creative means of heritage verification and community engagement, Roberts says, including reviewing funeral programs and collecting oral histories from aging Black baby boomers.

"Since I've started the project, I can tell you of five people that are gone that I once talked to," she says. "I've just been doing this work five years and five people are gone that I know."

When it comes to capturing their history, "it's a race against time," she says.

The Texas Freedom Colonies Atlas 2.0 maps out the research collected so far, with 357 locations currently plotted. View the interactive map, access the guidebook, and learn more about freedom colonies.

Next steps

The lack of information has also made it difficult to determine how many freedom colony residents or descendants have lost their land and who is currently at risk.

Roberts, her team, and Texas A&M University School of Law students plan to release an educational webinar this year to help with these issues. Luz Herrera, professor of law and associate dean for experiential education at the Texas A&M School of Law, says the webinar will distill the legal principles associated with the project — like property rights, historic preservation, and transfer of property — to viewers across various education levels.

Situations where a historic land ownership dispute isn't easily solved with a property title or deed may only be resolved via civil lawsuits. These can be costly, and it can be hard to find pro-bono counsel given that few lawyers practice in this area. The ownership issues associated with freedom colonies should be looked at holistically, not on a personal, case-by-case basis, she says.

"People don't plan and prepare and preempt title issues," Herrera says. "Planners should be talking about protecting property — not just buying and acquiring but protecting in terms of ownership interest."

Roberts hopes urban planners in the area — and others working with communities facing similar issues — will listen to historic preservationists and cultural resource managers who are already working to obtain information planners wouldn't have access to otherwise. This project could show urban planners how to enter communities and understand how they govern themselves, she says.

"The big thing I want to get across to planners is you need to validate what is and listen and depend on people with the expertise," Roberts says. "Working with the historic preservation community on a regular basis is better than waiting for a landmark commission meeting and a showdown."

Tatiana Walk-Morris is an independent journalist based in Chicago.